Latin America and the way I crossed

In February 2024, I started thinking about resigning. I was working for a medium-sized company based in Slovakia, traveling the world, and working remotely since the COVID era. After graduating in 2019, I applied for and received New Zealand’s working holiday visa, which allows you to work and stay in the country for one year. I had dreamed of buying a minivan, taking on seasonal jobs, and exploring the country before returning home to look for a full-time job. In short: taking a gap year.

Here’s how things unfolded:

My flight to New Zealand was canceled in January 2020 due to COVID, and the country remained closed to foreigners for another two to three years. Those granted this visa have one year to enter New Zealand, after which the one-year stay period begins.

With no other choice, I started applying for jobs back home in Slovakia. I landed one and, from that point on, I kept working. First on-site, then fully remotely.

Once I experienced remote work, I never wanted to go back. Over the next three years, I worked and traveled across more than 20 countries outside of Europe.

And there I was, sitting in my apartment in Chiang Mai, Thailand, wondering what was next. The dopamine rush was gone. I no longer felt like working remotely. Constantly moving, adjusting to new social circles, and maintaining a full-time workload had drained me. Yet going home and settling down wasn’t an option either.

Because in the back of my mind, there was still one thing left undone.

Taking a gap year.

In June 2024, I traveled to Guatemala to learn Spanish and live with a host family for a month. I enrolled in an immersion program at PLQE, determined to absorb as much Spanish as possible. The plan? Twelve months in Latin America. With all the paperwork settled back home, I was ready.

My host family consisted of a 75-year-old Guatemalan woman and her two grandchildren; none of whom spoke a word of English. My room was simple, and the school was in Quetzaltenango, a city located at 2,400 meters above sea level. Some days were freezing. There was no heating in the house, no thick blankets. When I said I am cold, I was given five thin ones to get me through the cold nights.

My room at the host family's house

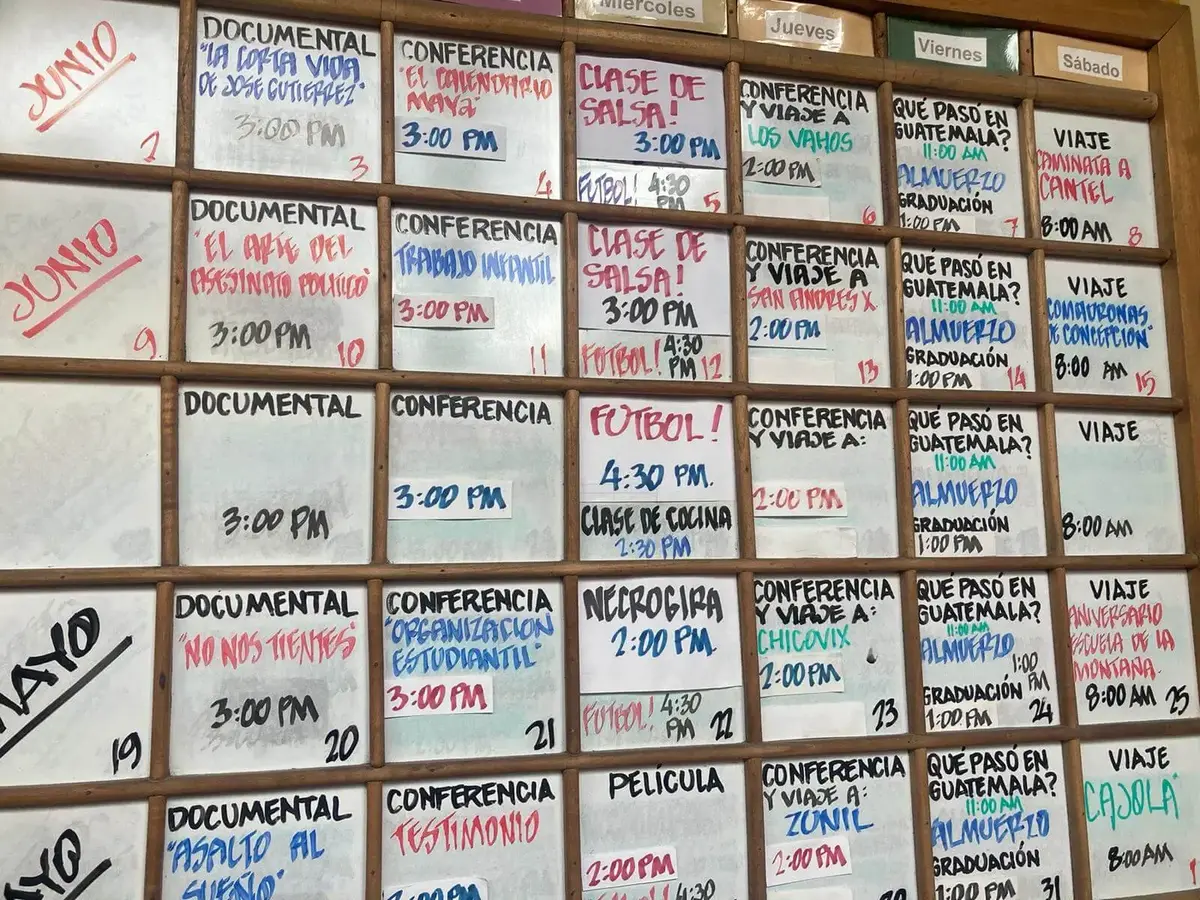

School schedule

Weekends were usually spent on day trips to nearby villages, guided by Alvaro; the school’s all-rounder, working as both a guide and maintenance guy.

After school, my backpacking journey was about to begin. Two weeks of traveling through Guatemala, putting everything I had learned to the test. I quickly realized that classroom Spanish and real-world Spanish were two different beasts. Locals spoke way faster than my teachers.

I even had my first dreams in (broken) Spanish. Lol.

6 photos

My time in Guatemala

The plan was to travel overland from Guatemala all the way to Ushuaia, Argentina; the southernmost point of South America. But if there’s one thing you learn while traveling, it’s that plans are made to change.

Before setting off, I didn’t give much thought to the different weather seasons along the way. At the time I was in Guatemala, all of Central America was in the middle of a heavy rainy season.

Talking to other travelers, I realized the rest of Central America was just as flooded. Adaptation is key, and if you want to enjoy traveling, you have to roll with the changes. I started reading about weather seasons in South America and quickly saw that if I went straight to Colombia, I’d hit the best season at every stop.

I had promised myself I wouldn’t take a single flight on this trip, but at that point, it just made sense. I booked a flight to Medellín and decided to start my overland journey from there. Arriving in Colombia with some Spanish basics was a total game changer. I saw other travelers wandering around clueless, but I could actually connect with people. Colombians are some of the most generous and funny people I’ve ever met. If I hadn’t learned Spanish before coming, this trip would have been a completely different experience.

4 photos

Random moments from Colombia

A month in, I found myself in Cali, learning salsa and planning my next move. Back in Medellín, during my first week, I met a French guy who couldn’t stop talking about Colombia’s Pacific coast. Every detail he shared pulled me in more and more. No tourists, no big hotel chains, just homestays, black sand beaches, and a mix of Indigenous Embera and Afro-Colombian communities. It didn’t sound like anywhere else in Colombia.

In Cali, I met Anita, a half-Peruvian, half-Swiss traveler. I could tell right away she was after the same kind of adventures as me, actually.. maybe even crazier. We both wanted to get to the Pacific coast, but without flying.

The thing is, Colombia’s Pacific region is one of the most dangerous parts of the country. I had already seen some pretty violent situations firsthand, so I was relieved I wouldn’t be going alone.

After asking around, we figured out we had to get to Buenaventura, a port town, and hope to find space on a cargo ship. There was no useful information online, and whatever we did find was years out of date.

We got lucky. Within 30 minutes of arriving at the port, we met Alejandro, who introduced us to a captain with two spots left on his boat. They were leaving in a few hours. We couldn’t believe it.

3 photos

Cargo ship journey

The journey was 170 kilometers across the open ocean. It took over 26 hours. When we finally stepped off the boat, we could barely walk in a straight line, stumbling around like we’d downed eight beers back to back.

And then, I got it. I finally understood why the French guy was so obsessed with this place.

Everything he said was true, and on top of it, we had arrived right in the middle of whale season. Sitting on the beach, we watched whales jump out of the water every half hour. Instead of packed dorm rooms, we found only homestays with the friendliest locals. Fresh tuna for every meal. Hikes along the coast to different villages, timing the tides so we could cross rivers along the way. It all felt like a movie.

And at that moment, I knew that this is it. These are the places I need to aim for on my travels.

Walking 20km through the coast of El Chocó

Looking at a map, Ecuador might seem like a small country. But the landscape diversity is something else.. massive volcanoes, a stunning coastline where you can surf, snorkel, or watch whales, and the vast Amazon rainforest to the east.

By this point, I was used to long overnight bus rides, so I hopped on a 16-hour journey to Montañita, a small coastal town. When we arrived at 5 am, it didn’t look anything like the famous surf spot I’d heard about. It looked abandoned. There wasn’t a single soul in sight. The bus terminal didn’t even exist, it was just a small, empty area on the outskirts of town.

I walked two kilometers into the center and finally found my hostel. It was locked up and completely dead.

Most backpackers in South America follow what’s called the “Gringo Trail,” traveling either north to south or vice versa. But Ecuador wasn’t on many people’s route. Those who did visit usually skipped the coast, especially after the news of people being found butchered and dumped under bridges in black plastic bags. The region had become more dangerous due to its proximity to Guayaquil, a massive port city with 2.65 million people and a key hub for narco trafficking. To top it off, I was there in the middle of the off-season; half the businesses were closed, and the place felt like a ghost town.

Horseback riding in Cotopaxi national park

I sat down outside the hostel, exhausted, when someone finally opened the door. It was a volunteer heading to the bathroom. He let me check in early since, as he said, “literally no one is staying here right now.”

Then he asked for my passport.

I reached into my bag. Checked all my pockets. Looked again.

It wasn’t there.

I was 100% sure I’d left it in the last town when I bought my bus ticket. It was 6 am. I was dehydrated, stuck in a ghost town, and officially freaking out.

I called my last hostel but no one answered. I tried calling the bus terminal, but no one picked up either. I had two options:

Take a bus to Quito, go to the embassy, fill out a bunch of paperwork, get a temporary travel document, and fly home to apply for a new passport; or simply keep searching.

I ran back to the spot where the bus had dropped us off, hoping it was still there. It wasn’t.

So I started asking random people on the street if they had seen a yellow-and-white bus with “102” on the side. That was the only detail I could remember. After a few failed attempts, someone finally told me that overnight bus drivers usually eat at a specific restaurant on the other side of town.

I ran there.

Inside, I scanned the room, looking for a familiar face. And then I saw him.

The bus driver was finishing his breakfast. I walked up to him.

“Excuse me, were you driving bus 102 this morning?”

He looked at me like I was some confused gringo, gave a small nod, and kept eating.

One of the guys at his table made a money gesture with his fingers.

I dropped $20 on the table. “That’s for the table,” I said, then shoved another $20 into the driver’s hands.

He smirked. “Is it a small red Patagonia wrist bag with an analog camera?”

My heart dropped.

Wait. Why is he talking about my camera? What about my passport?!

“Please, can you finish eating and show me the bag? I need to check if my passport is inside.”

He finished his meal, then led me outside to the bus parked on the sidewalk. He opened a small compartment next to the driver’s seat and handed me the bag.

It was mine.

I opened it and my camera was there. My passport too.

We both burst out laughing. He never realized there was a passport in there, and I had no clue I had lost my camera bag along with it.

I couldn’t believe it.

I wasn’t going home.

4 photos

My first 24-hour bus ride. What a day. I think I tried every possible sitting position on that chair. We finally arrived in Tarapoto, and from there, I planned to get to Yurimaguas. The closest town to the Amazon River you can reach by vehicle.

This was the place I kept talking about to everyone I met. For some, it’s about seeing the Seven Wonders of the World. For me, it’s about collecting unique experiences, and this was it.

In Yurimaguas, cargo ships transport people along an 600-kilometer route to Iquitos, cruising small rivers for about three days. Just before reaching Iquitos, those rivers merge into the massive Amazon River. Iquitos is the world’s largest city that can’t be reached by road, and I was beyond excited to experience the journey there.

Wandering around the port, I asked different people when the next cargo ship would depart, but every answer was different. Then I met this guy, César, trying to sell me a private Amazon tour. I didn’t even consider it at first, but after struggling to find a straight answer about the ship’s departure, I went back to him.

“Help me get a ticket, and I’ll come with you to your office to talk about the tour.”

He nodded and immediately started making arrangements. A few minutes later, he helped me set up my hammock on one of the cargo ships, set to depart in eight hours. Workers were loading chickens, boxes of rice, and bananas. Pretty much everything imaginable.

César took me to his place on his tuk-tuk. His house was in rough shape. He led me to a small room, pulled out a map, and started explaining his tour. His wife was cooking dinner in the background. It clearly wasn’t an official tour company, but I wasn’t too suspicious. The price was incredible - 120 soles per day for a private wild camping trip in the Amazon.

“Too good to be true,” I thought.

He asked me to pay in cash upfront. To make sure he wasn’t going to scam me, I asked his wife if I could stay for a family dinner. She was making Juanes, a traditional Amazonian dish, and I wanted to try it. I ended up spending the whole afternoon with them. Drinking beer, eating Juanes, and swapping travel stories.

3 photos

Cesar, hammocks, toucan, the Amazon starter pack

Back at the port, the ship was still being loaded. I started feeling a bit nauseous and feverish, so I lay down in my hammock. I woke up in the middle of the night. It was 2am, and we were still docked. No one was loading anything anymore, yet the boat hadn’t moved.

It finally started sailing at 7am. I was the only tourist on board. The rest were families, young girls with newborn babies, some people sleeping on the rusty metal floor, others in hammocks.

For the next three days, I did nothing but sleep, observe, play cards, joke around with kids, and watch sunrises and sunsets.

In the middle of the night, I was woken up by César’s cousin, José. He helped me pack my things, and we walked to his hut, where he introduced me to his community. We repacked for five days of wild camping and went to sleep. Early the next morning, we were set to head deeper into the jungle on his small fishing boat.

3 photos

The next five days were unreal. Visiting indigenous communities, night hikes, fishing, building shelters, and speaking Spanish non-stop.

On the way back to José’s house, we still had about four hours to go by boat when I started feeling sick again. The heat and humidity were unbearable, and this time it was worse. I was trembling, freezing despite the heat, and then came the vomiting.

José offered to let me stay at his place until I got better. Obviously, I accepted.

But things got worse.

Two full days of extreme vomiting, diarrhea, and barely being able to drink water. Meanwhile, José had turned out to be a full-blown alcoholic, spending the entire time getting blackout drunk instead of helping me.

I had to get out.

A few hours later, I found someone reliable with a boat and made it to Iquitos. I went straight to a doctor.

“Double infection. Giardia and Salmonella,” he said.

I was given medication and told to book a private room and stay hydrated.

The next seven days were spent “wild camping” in my bathroom, watching TV, and eating nothing but white rice with bananas. It took almost three weeks before I could eat a full meal without immediately running to the toilet.

yeah Amazon.. I think I’ll never forget.

After the Amazon, I reunited with my old high school friend, Tomáš. He was also traveling solo through South America on his sabbatical, chasing the same dopamine-fueled adventures as me. After three weeks of off-road biking through the Peruvian Andes, crossing mountain passes above 4000m, we thought we were ready for a high-altitude challenge.

4 photos

Our motorbike trip to Machu Picchu

Chilling in our first Airbnb of the trip, soaking up the cheap luxuries of La Paz, we set our sights on Huayna Potosí, a 6088m mountain just outside the city. It’s a popular spot for backpackers wanting a taste of high-altitude mountaineering in a relatively safe environment. We couldn’t have been more excited. We’d been living above 3500m for weeks, so we naively booked the 24-hour option instead of the standard three-day trek. Most people take the longer route to acclimatize properly and increase their chances of reaching the summit, but we weren’t fazed.

“They don’t know us,” we thought. “We grew up hiking our whole lives. Why would we have a problem?”

Well, we weren’t entirely wrong, but altitude is real, and it doesn’t care how many mountains you’ve hiked. If you underestimate acclimatization, it will kick your ass.

We set off for the lower base camp at 4700m, where our guides and gear were waiting. After a quick briefing, we packed up and began the trek to high camp at 5000m. We arrived around 4 pm, where our chef served hot veggie soup and coca leaf tea (supposedly good for altitude). We had a few hours to rest before the summit push.

At 23:30, the door flew open.

“¡VAMOS, VAMOS, VAMOS!” our guide shouted.

We looked at each other, clearly not ready for what was coming next. We would’ve given anything for a warm bed and a full night’s sleep. But minutes later, we were outside in the freezing darkness, climbing.

At first, we kept a steady pace. But after two hours, Tomáš started feeling dizzy. Then came the vomiting. I had massive stomach cramps and knew it was only a matter of time before I’d be next. Meanwhile, our guide stood off to the side… casually watching TikTok.

Now, it’s a hilarious image. Tomáš on his knees, gripping his ice axe, puking his guts out, while our guide mindlessly scrolled on his phone. But at that moment, I couldn’t believe my eyes.

At around 5500m, Tomáš decided to turn back. We waited for another group to pass so I could continue with them. Luckily, a Norwegian girl and a Canadian guy (both super fit) agreed to let me join. Their guide, Erwin, was 27, climbed this mountain 3-4 times a week, and lived in a village near the lower camp.

Ervin, my new guide

We pushed on. The steepest section of the climb drained me completely.

“How high are we?” I asked, gasping.

“5900m.”

I turned to look at the Norwegian and Canadian, both smiling, seemingly unfazed. I wished Tomáš was still here so we could descend together. Then, out of nowhere, I saw him lying on the ground, Luis pouring hot tea into his mouth.

I couldn’t believe my eyes. Again.

What the hell was he doing here? He had been vomiting his soul out two hours ago!

At that point, he finally gave in and started descending. I wanted to go with him, but I was too stubborn. I continued with my new group.

The last 200m felt like an eternity. Every step took three massive breaths. But the summit was close.

At 7:12 am, we stood at the peak, hugging each other.

3 photos

It had been a long time since I felt that kind of happiness. My soul was smiling.

After exploring the salt flats of Uyuni and the Atacama, (the world’s highest desert) we crossed into Chile. From there, it’s a straightforward route: hop into San Pedro de Atacama, then work your way down south toward Santiago.

I stood at a crossroads. Should I keep heading south? Patagonia was calling, but I left all my camping gear except hammock and thin sleeping linen at home. The rentals were ridiculously expensive. I had no idea what I was thinking when packing for this trip. One thing I learned? It’s nearly impossible to pack yourself great for a year-long journey that spans everything from surf towns to major cities to high-altitude mountains.

So, I changed my plans again.

I set my sights on Brazil.

Most travelers follow a well-trodden path: another 1000 km south to Santiago, then crossing into Mendoza, Argentina. It’s one of the most scenic border crossings at 4000m, with the chance to glimpse Aconcagua, the highest mountain outside of Asia. From there, they head to Córdoba, Buenos Aires, maybe hop into Uruguay, and finally make their way to Brazil.

It’s a solid plan. But I wanted something different.

While searching online, I stumbled upon an article mentioning an occasional bus to Jujuy, a province in northern Argentina. It was a 12-hour ride, but there was no official schedule. Curious, I went to the bus terminal to ask.

By sheer luck, I managed to grab one of the last four seats. The route had only recently been reinstated after years of border issues. That was all I needed to hear, I didn’t linger in Chile. I knew I’d be back one day, but this time, I wanted a different kind of adventure.

Argentina was wild. ATMs were either empty, out of service, or had a withdrawal cap equivalent to 50 USD, with a fee that ate up a third of that. Others clued me in on a trick: foreigners with bank accounts in stronger currencies could send money to themselves through Western Union and pick it up at a way better exchange rate with minimal fees.

So, I wired myself $300.

What did I get in return? Four massive wads of cash, all in 1000-peso bills. Nearly 400 of them.

Western Union, if you look closely at the girl, you can see the wads of cash.

I felt like a millionaire. But in reality? Argentina was more expensive than ever.

I continued moving through northern Argentina, eventually making my way toward Iguazú Falls. “Why not visit Paraguay?”, I thought. It’s one of the least-traveled countries by backpackers, and I found the idea of going where few others go oddly exciting.

In just ten days, I had passed through Chile, Argentina, Paraguay, and was already on my way to Brazil.

For the first time, I questioned myself: What’s the point of traveling like this?

I felt regret.

4 photos

After Iguazú Falls, Florianópolis, and Rio de Janeiro, I hit a wall. Traveling without a purpose was starting to feel empty, and I knew I had to change the way I was doing it. I needed a goal.

So, I signed up for a two-week surf camp in Itacaré, a small surf town in northeastern Brazil. Everything was perfect. Surfing every day, eating Açaí, practicing Portuguese; until I almost broke my rib. The pain was so bad I couldn’t even lift my arm. I tried pushing through for another two days, but even painkillers couldn’t make the waves enjoyable. Luckily, the surf school let me reschedule for another camp in three weeks. I decided to rest.

That’s when I stumbled upon a place I’d never even heard of: Chapada Diamantina.

A vast mountain range with otherworldly vegetation, massive canyons, reddish-brown rivers, and hidden caves. The area offered everything from short hikes to multi-day treks. Getting there from Itacaré, though, was an adventure in itself. First, an 8-hour bus to a transfer point, then another 7-hour ride.

I took two slow days to explore the area and soon met a German guy who had just finished a four-day trek alone.

That caught my attention.

Everyone I had talked to insisted the trek required a guide, and the price was steep. More expensive than treks in Nepal or Peru. But this guy had done it solo. It didn’t take long for us to get along. He gave me all the info I needed: GPX files for offline navigation, chlorine tablets to purify river water, even a stash of leftover protein bars. He was excited to meet someone as crazy as him.

That night, I set my alarm for 5 am, repacked my bag, left my bigger backpack in storage at a local campsite, and got ready to hike 80 km through the real Brazilian wilderness.

On the first day, I didn’t see another soul for the first 25 km. More than a physical challenge, it was a mental one. My mind kept going back to the German guy’s warning about venomous snakes, he had almost been bitten by one.

3 photos

Vale do Pati, the most popular trek in remote Brazilian inland.

I camped in a remote valley, in the backyard of a local family’s house. Thirteen families still live in the valley, offering basic accommodation and meals to guides and their clients. They weren’t exactly thrilled that I was trekking solo. The other hikers kept asking how I was managing without a guide, while the guides themselves seemed annoyed, trying to maintain the idea that hiring one was mandatory.

But the families? They didn’t care.

They were just happy I was enjoying their land and even gave me tips on hidden spots to check out.

I spent another two weeks hiking through Chapada Diamantina. My rib had healed, my energy was back, and all I could think about was returning to Itacaré.

For the first time on this trip, I was going back to a place. Back to a routine. Back to friends waiting for me. It felt good to not have to make small talk with strangers every day.

A few days later, I finished my surf camp. And I felt it.

Saying goodbye

I was ready to go home.

We spend so much of our lives chasing goals. In our careers, deadlines make them necessary, leaving little room for reflection. But even in our personal lives, we often fall into the same trap. Focusing on the destination rather than the journey itself.

Coming home after eight months of full-time travel, I felt an unexpected sense of disappointment. Why? Maybe deep down, I had expected this gap year to change something in my life. I had been longing for it for so long. But now that I was back, everything was the same.

So, what was bothering me? Expectations.

I didn’t make it all the way to the southern tip of South America like I had originally planned. I changed my route in Guatemala, choosing to fly over Central America instead of crossing it overland as I’d intended. Maybe that was it. The fact that I didn’t follow through with every single plan I had made.

But then I asked myself: Would it have made a difference?

If I had reached the end of my route exactly as planned, would I feel any different? Probably not. The real issue wasn’t where I went or how I got there; it was my mindset. I was too focused on what waited for me at the finish line, caught up in expectations, instead of fully embracing the moment.

That’s the biggest lesson this journey taught me.

Traveling isn’t just about seeing places; it’s about being exposed to yourself. Sitting with your thoughts, facing boredom, experiencing discomfort. In a world where we constantly distract ourselves, we rarely get that chance anymore.

So, if you’re still wondering whether you should explore the world on your own… do it.

It’s therapeutic.

Latin America, June 2024 – February 2025